|

| ||||||||||

|

Mon, 19 January 2004

Back From Exile, Kurds Demand Political Power

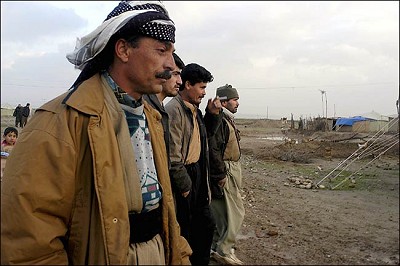

It is not the homecoming they expected. Driven from Kirkuk more than a decade ago by Saddam Hussein's government, they eke out their days waiting for what they say is their due. "We lost years of our lives, so we need compensation," Lukman Abdul-Rahman, 39, said as he stood surrounded by a dozen men, all nodding vigorously. "The Kurds have suffered much more than others, and we should be the government's top priority." Kurdish demands for political rights and reparations have suddenly emerged as one of the most pressing issues confronting American officials, who are trying to create an Iraqi transitional government. Kirkuk, an oil-rich city just outside the northern Kurdish region, is the linchpin of the Kurds' drive to retain their autonomy. In Kirkuk, the campaign by Kurdish leaders for broad governing powers and claims by families for property restoration are feeding ethnic tensions that could explode. That prospect seems even more likely if Kirkuk's political future is put to a vote in the area, an idea that Kurdish leaders and some members of the Iraqi Governing Council are now supporting.

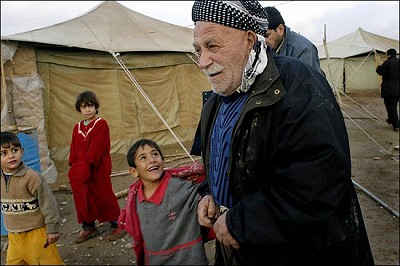

Recent protests by Arab and Turkmen residents against such Kurdish claims have already ended in gunfire and death. American soldiers have stepped up street patrols, and their searches of the headquarters of various political parties have uncovered illegal weapons. A bomb exploded near the headquarters of one of the two main Kurdish parties on Jan. 11. Thousands of Kurdish and a few Turkmen families have flooded the city to demand land stripped from them under Mr. Hussein. Many live in squalor, some in tent villages, others in ramshackle public buildings. Arabs paid to move here under the former government's campaign to make the region Arab fear that Kurds will exact vengeance, and many have fled. For the two main Kurdish parties, this change in demographics bolsters their claim that the Kurdish autonomous region should envelop Kirkuk. Kurdish leaders believe they need the oil fields and rich agricultural land nearby to keep the Kurdish region economically independent. But no political group is willing to cede control of Kirkuk to the Kurds. The Americans are trying to control the situation, said Joost R. Hiltermann, a Middle East expert with the International Crisis Group, a conflict prevention organization, but "it could really get out of hand."

Mr. Hiltermann said: "The Kurds have to make a basic decision — to go with the Americans or not. If they go with the Americans, they'll get support, but not everything they want, namely Kirkuk." L. Paul Bremer III, the top American administrator in Iraq, has met twice recently with Kurdish leaders to ask them to back down from their demands, including from their claims to Kirkuk, only to be rebuffed. Fatal clashes have flared up, with Arabs, Kurds and Turkmens each claiming the city as their own. "The ambition of the Kurds is not a new ambition," said Esmail al-Hadidi, a deputy mayor of Kirkuk and a member of one of the city's oldest Arab families. "But we need Kirkuk for everyone. The Arabs here are not willing to let Kirkuk go to the Turkmen and the Kurds." At a nearby youth and sports center for Turkmens, a banner proclaims that "Kirkuk is a Turkmen city and will stay a Turkmen city forever." Powder-blue flags with a crescent moon and stars, similar to the Turkish flag, are displayed inside. Muhammad Arga Oglo, 30, the director of the Turkmen Student and Youth Union, greeted a visitor while sitting beneath a poster of Ottoman horsemen slaughtering their enemies in a river of blood.

"We have the right to express ourselves by any means," he said. "If it's necessary to defend ourselves, we will." Thousands of Arabs and Turkmens held a rally at the end of December against the Kurdish demand for autonomy, and it ended in gunfire between protesters and Kurdish guerrilla fighters. Four protesters were killed and 24 wounded; other killings have followed. Officers with the 173rd Airborne Brigade, which controls the city, have asked leaders of the main ethnic groups to stop the violence. But during a sweep of the offices of the Kurdistan Democratic Party, American soldiers found a cache of weapons that included 17 Kalashnikov rifles and three rocket-propelled grenade launchers, said Maj. Douglas Vincent, a spokesman for the American-led forces. Major Vincent said soldiers also found Kalashnikovs at the headquarters of the Patriotic Union of Kurdistan, the other main Kurdish party, and at the Iraqi Turkmen Front. Najat Hassan, the local head of the Kurdistan Democratic Party, denied that American soldiers had found illegal weapons. He also defended what he called the right of Kurds to govern the city. "Kirkuk is a historical and geographical part of the Kurdish region," he said.

Mr. Hassan explained his own claim, dating back a half-century, to a one-story home in the city center. In 1986, he said, Mr. Hussein's government seized his home and handed it to an Arab woman. Mr. Hassan moved north to the Kurdish city of Erbil and lived there until the American-led forces took power last spring. He said he was now waiting for the Governing Council to repeal a law that allowed the confiscations. "I am a patient man," Mr. Hassan said. "But what about the others?" A local government office has received 3,000 property claims, said Hassib Rozbayani, an assistant mayor. A mile from the tent village where the returning Kurds live lies the neighborhood of Qadisiya, where over the decades many Arab migrants have built concrete homes. Ahmed Abdullah, 27, an Arab, said his family was paid $33,000 to move here from Diyala 25 years ago. Standing by his vegetable stand, he pointed to a residence across the street, which he said Arab owners recently sold to move south to Basra, fearing the house would be seized. In the last months, Mr. Abdullah said, graffiti had appeared on several houses saying, "Your homes will be your graves."

| ||||||||||

|

|